Colonial traces - always around the corner

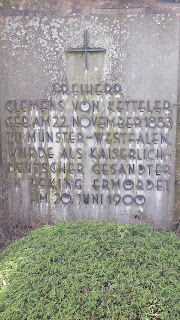

When I was looking at Zaifeng and the Boxer Rebellion, it became clear to me that Münster was a city which still had traces of the conflict's beginnings. Germany's Ambassador Clemens von Ketteler, who was killed in the initial stages of the conflict, was from here (in fact he went to the same high school that my kids are now attending). And I found out that he is buried in the central cemetery here as well. The city also built a commemorative monument to him, which is in the palace gardens.

Having chatted to the family about this, we decided that a family outing to see these sites was in order. A trip to the cemetery here is actually not too ghoulish - it's exceedingly well looked after, with each grave site like a small landscaped garden plot. And the palace garden is always a favourite with the kids, no matter what we're doing. There's some hot houses, the old star moat and the palace itself. This week the fair - 'Send' - is also in the palace grounds. So they didn't take too much convincing.

There'S much I could say about these sites, parsing their language and position. But that's not what struck me as I wandered around. Instead, what struck me is that in Germany, the colonial past is historical. There are of course current postcolonial debates about things like reparations for Namibia for the genocidal warfare conducted there, or the provenance of items that might end up in the Humboldt Forum, or how to sensitively repatriate human remains collected by German anthropologists in colonial sites.

As I said to some colleagues who were visiting me in Adelaide at the beginning of last year, however, this is quite different to knowing that your entire nation, the only physical environment that you know of as your home, was built on the dispossession and near destruction of the communities that lived there before Europeans.

That is not to say that Australia's enduring colonial stain invalidates the importance of Germany's postcolonial reckoning with its colonial crimes. It clearly doesn't. But here I have to look for colonial traces in hidden corners. Monuments, gravesites, vanishing street names, museums.

I know the arguments: 'Hamburg / Bremen / Berlin / wherever profited because of its place in the global constellation of imperial relations'. But, put simply, at home, the entire society, my entire society, is built on stolen land. Every house, every sporting field too. Australia has a black history and its loss / erosion is visible everywhere.

Without wishing to offer too much demonstrative self flagellation, this makes my job, as a white, settler colonial descendant researcher into colonialism, all the more complex. I am seeking to understand the origins of European imperialism, not as some kind of abstract phenomenon, but as someone implicated in the genocidal foundations and enduring discriminatory structures of the society of which I am a part.

To my mind, there are two potentially fruitful approaches to this dilemma. 'Decolonising' and 'postcolonial'. As I say here, I think a lot of what is being called decolonising is in fact postcolonial work or even neither. And I also don't buy the idea that only decolonising is material, while postcolonial is some kind of moral gymnastics. I do, however, have too much respect for decolonisation as a position to pretend that normative 'decolonising the mind' is in the slightest bit decolonisation unless it is accompanied by a substantive, material decolonisation. Normative decolonisation by itself just strikes me as liberal ideology and disingenuous.

Real decolonial approaches (of the Tuck and Yang style, not the 'here's the new buzz word I'm going to apply it to what I already do' variety - a fate that befell intersectionality as a term. But I digress...) seem to dwell on the first chapter of Fanon's Wretched of the Earth, /and in particular Sartre's radicalisation of Fanon in his introduction to the same. It has a 'burn it all down' approach to colonial successor societies that encourages a kind of anachronistic separatism as a millenarian road to salvation.

I understand the mood, but that's not a project I can unstintingly support, despite its invigorating radicalism. Perhaps that's self serving. But I don't think that the settler colonial project will end that way. That's not to say that I think weepy, liberal 'reconciliation' as an endgame is the right approach either. These approaches tend to think of reconciliation as a moment, where we all look at each other, admit our sins and then move on, cleansed of our genocidal past. Nothing material has changed here and I don't think it's a productive strategy, just liberal settler colonial PR.

Instead, I'd argue for the postcolonial hopefulness of Homi Bhabha (old hat for some) and the later part of Wretched of the Earth (which no-one reads or quotes), which asks what happens once the embers of the purifying fires cool. Bhabha in particular acknowledges that with colonisation something was irretrievably broken, and that Australia's settler colonist forebears broke it. Crucially, Bhabha then hunts for material ways not to reverse this, or 'come to terms with it', but to make a new thing, incorporating this hard won knowledge into material programmes for the future.

In the Australian context, to begin with, this might look like what was argued for in the Uluru Statement which has going for it that it was built by Indigenous hands and minds (which is not to say that it's a 100% consensus document). As it shows, creating the new thing should centre on the material facts of territorial and political sovereignty, not just 'acknowledgement.'

Conservatives would call all of this 'virtue signalling', but that's just name calling that fails to address the substantive issues. For their part, Tuck and Yang would probably call this an attempt to 'preserve settler colonial futurity' and this whole blog piece would fit under the heading 'settler colonial moves to innocence'. By their terms, fair enough. But it's not necessarily a zero sum game, where every step can only beneift one of two communities. And I hardly think that my bald statement of the facts counts as a 'move to innocence'.

Australia will never be a place where, like Germany, the settler colonial past has to be looked for or teased out. It will always be one of many places where dispossession and genocidal processes created a settler society. But some modest material options for creating a collective future have been put on the table by Indigenous people looking to move the situation forward. It's incremental and pragmatic. But magnifying these voices and trying to remove structural and incidental obstacles for them is perhaps a start.

Comments

Post a Comment